1 September 1650

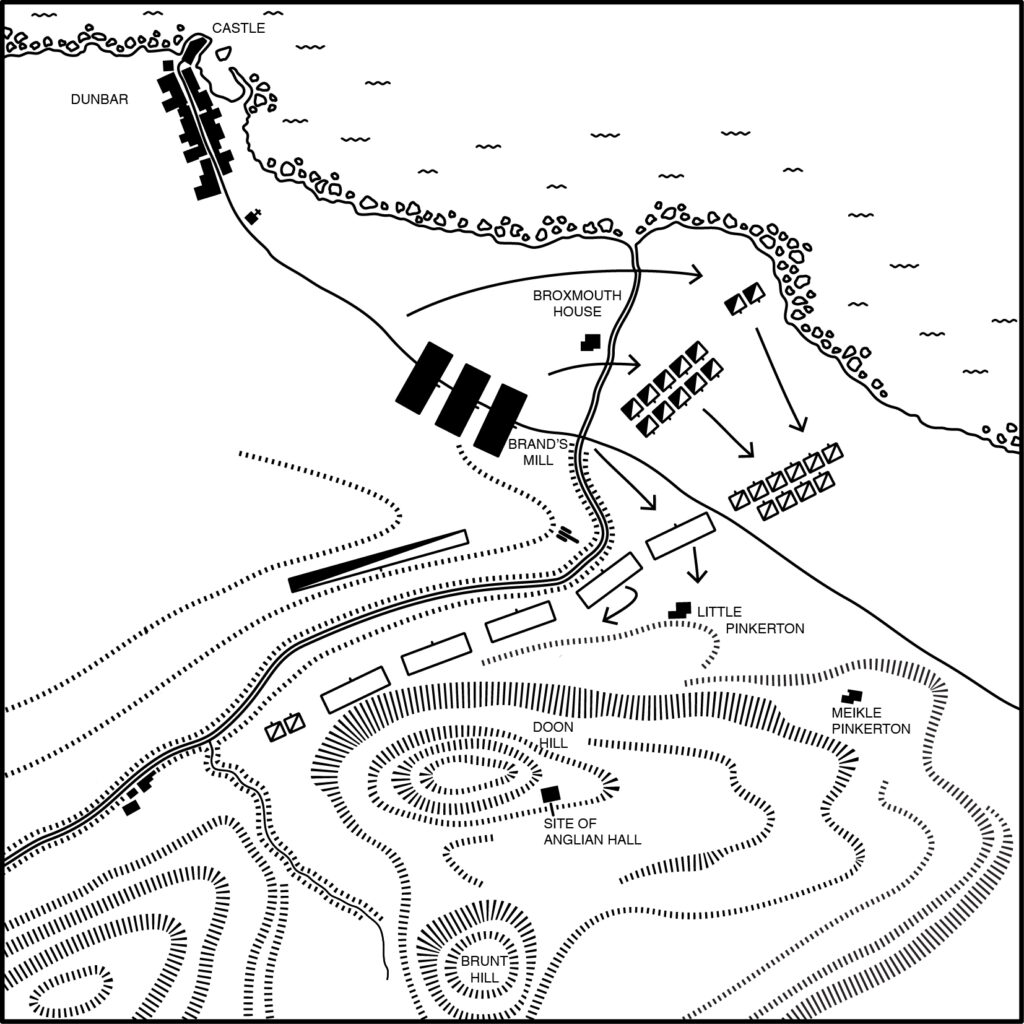

The armies arrive outside Dunbar on 1 September from the direction of Haddington. Cromwell’s forces draw up for battle facing towards the south, probably parallel with the modern A1 motorway. But Leslie does not intend to face him today, and instead draws his army onto the dominating summit of Doon Hill. Cromwell accordingly shifts his lines , using the steep ravine of the Brox Burn to protect his front whilst keeping the town and harbour secure to his rear. When the wind dies down sufficiently, Cromwell’s rain-soaked soldiers encamp to the eastern or south-eastern side of the town.

2 September 1650

After an uncomfortable night on the hilltop, the Scots move some of their strength onto the lower slopes north of Doon Hill. This provides a degree of shelter from the elements and allows them to fully control the road from Dunbar to England. Cromwell is now trapped. The English picket east of the Brox Burn is driven in by Scots lancers, and as the poor weather continues the main body of Leslie’s army completes the descent from the hill. Cromwell and his commanders observe the Scots motions from their headquarters at Broxmouth House, and weigh up their options.

In the evening a council of war agrees to attempt a break-out by attacking the Scottish flank the following morning. Under cover of the darkness and the rain, the English army redeploys into a massed column along the road, with a further brigade moving north towards the seaward ford. Okey’s Dragoons are posted along the Brox Burn to screen the movements.

Despite the weather, the Scots stay alert long into the night. Not until the early hours of the morning is the army stood down, with the men obliged to find what little rest and shelter they can in the open ground. David Leslie heads to bed at Spott House, on the extreme left of his lines.

3 September 1650

Between 4-5am the English completes its redeployments and pushes cavalry across the fords between Broxmouth and Brands Mill, sweeping away the unsuspecting Scottish pickets and clearing the way for the general assault.

The attack is spearheaded by the heavy horse, who cross the burn and dress their lines before advancing towards their unsuspecting adversaries. Leslie has however massed his own cavalry on his right, and despite their initial surprise the Scots horse rally and hold their ground. This huge cavalry battle involves around 9,000 horses and riders (equivalent to the whole population of Dunbar today). Eventually, Cromwell’s disciplined troopers drive the Scots back and secure command of the coastal flank.

Meanwhile, Monck’s infantry brigade has crossed the burn and charged Lumsden’s unprepared foot levies. The Scottish infantry flank is quickly shattered, but Campbell of Lawers’ Brigade is able to form its battalia and counter-attack. Monck’s men are pushed back away, but are reinforced by Pride’s Brigade and the Scots are in their turn driven back him the slope towards Little Pinkerton. At this point, Cromwell’s triumphant cavalry appear on their flank: with no Scots horsemen left to oppose them, the Ironsides are able to sweep down on the Scottish infantry and break their resistance.

Further along the Scottish line, the infantry regiments are too far apart too offer proper support to their fragmenting flank, and unable to re-deploy in the ground between Doon Hill and the Brox Burn ravine. Bombarded by English artillery from across the ravine and seeing their comrades routing towards them, the Scots centre disintegrates as the sun rises. Cromwell’s cavalry dominate the field, preventing the Scots from rallying or reforming, and large numbers begin to surrender. Those fleeing are cut down mercilessly, and the shattered remnants pursued 8 miles towards Haddington.

David Leslie was in Spott House when Cromwell’s attack began, 1.5 miles away. By the time he was in the saddle his flank had probably already collapsed. He seems to have played little role in the battle, unable to affect the course of events as his army disintegrated. He escaped west towards Edinburgh.

Cromwell himself claims that 3,000 Scots were lain on the field, and only 50 Englishmen. His figures may be exaggerated, and do not include the English wounded. It was, nonetheless, a total disaster for the Scots. The field army which had defied Cromwell and protected Edinburgh for six weeks had effectively ceased to exist. It had taken about an hour.

The video summary below (prepared by Durham University) provides an impression of the battle imagined from the perspective of a Scottish soldier:

A number of re-enactments of the Battle of Dunbar have been held since the 1970s, the most recent being in 2016 and 2019. The video below shows some of the highlights from 2019, include the recreation of the skirmish at the “poor house”.